- Home

- Lyonel Trouillot

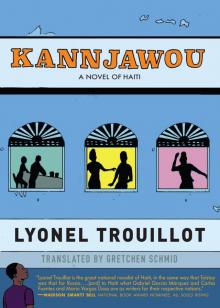

Kannjawou

Kannjawou Read online

To Sabine and Marie,

To Joanna,

To Maïté and Manoa, to share with Mehdi, Jean-Lou, and the AJS gang,

To the poet Jeudi Inéma, who brought my attention to the life of the great cemetery

Original French language edition Copyright © Actes Sud, 2016—Arles-Cedex

Original title: KANNJAWOU

Copyright ©2016, Lyonel Trouillot

Translation by: Gretchen Schmid

Cover and Interior Design: Evan Johnston

This is the first English Language Trade Paperback Edition English language copyright (c) 2019, Schaffner Pres

No part of this book may be excerpted or reprinted without the express Written consent of the Publisher.

Contact: Permissions Dept., Schaffner Press, POB 41567 Tucson, AZ 85717

ISBN: 978-1-943156-78-8 (Paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-943156-79-5 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-1-943156-80-1 (EPUB)

ISBN: 978-1-943156-81-8 (Mobipocket)

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Information, Contact the Publisher

Printed in the United States

To dance these blues with you, madame,

The earth would put an end to its horrors of glory

The blood the prisons the wreckage

The bread that was never daily for everyone

The battles with no tomorrow

And the sorrows forgotten in the ashes

—RAYMOND CHASSAGNE

If you buy me a drink, we’ll see this thing through

You’ll be my friend, for at least a few moments …

—BERNARD DIMEY

ALSO BY LYONEL TROUILLOT

NOVELS

Les fous de Saint-Antoine

Le livre de Marie

Rue des Pas-Perdus (in English: Street of Lost Footsteps, University of Nebraska Press, 2003)

Thérèse en mille morceaux

Les enfants des héros (in English: Children of Heroes, University of Nebraska Press, 2008)

Bicentenaire

L’Amour avant que j’oublie

Yanvalou pour Charlie

La Belle Amour humaine

Le doux parfum des temps à venir

Parabole du failli

Ne m’appelle pas Capitaine

SHORT STORIES

Les dits du fou de l’Île

POETRY

Depale

La petite fille au regard d’Île

Zanj nan dlo

Ra Gagann

Éloge de la Contemplation

Pwomès

NONFICTION

Haïti

Lettres de loin en loin : Une correspondance haïtienne

ANTHOLOGIES

Anthologie bilingue de la poésie

créole haïtienne de 1986 à Nos Jours (co-editor)

I

“IT’S WHEN YOU FOLLOW YOUR FAULT LINES, CHOOSING THE APPEARANCES OF THINGS OVER THE THINGS THEMSELVES, THAT YOU TAKE THE WRONG PATH AND MAKE A FOOL OF YOURSELF.”

I don’t know where Mam Jeanne finds phrases like that. If what she tells us is to be believed, all she knew in her childhood was the gray cover of the syllabaire1 and a book of mental arithmetic that stopped at the rule of three. Perhaps adages do have some truth to them, age sometimes bringing with it reason. And old women are the ones who begin speaking like a book in grave times, even though they’ve never read anything.

When we’re sitting on the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house, it’s one of our favorite subjects, me and the little professor: ages and paths. Why are you coming here and not going there? Which part of you controls the path that you’re following? Do all steps lead somewhere? Popol, my brother, says that I took my first step at one year old. That means I’ve been walking for twenty-three years. I know exactly how many steps are between the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house and the main entrance to the great cemetery, between the great cemetery and the linguistics building, between the linguistics building and the branch of the commercial bank where the armed foreign service members in uniform sometimes go, between the branch of the commercial bank and my sidewalk curb. I also know that, ever since childhood, all of my steps bring me to the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house. My place of meditation, where, as the sentinel of lost footsteps, I spend my time pondering the logic of pathways. Sentinel of lost footsteps. The little professor is the one who calls me that. And yet he’s just like me, only thirty years older. Or I’m like him, thirty years younger. Sentinels of lost footsteps. We spend a lot of time talking about paths, without being able to change anything about them. And in the evenings, we ask ourselves questions that remain unanswered. What path of poverty and necessity could have led a boy born in a Sri Lankan village or a shantytown in Montevideo to find himself here, on a Caribbean island, shooting at students, robbing laborers, obeying the orders of a commander who doesn’t even necessarily speak the same language as him? Of what use is the part of his salary that he sends home to a mother or a wife? Did he rape someone for the first time in his home village, maybe a childhood friend or a cousin? Or is that a habit that comes with estrangement, with the discomfort of barracks in an unknown country? Did he learn from his peers? When you’re dying of boredom and in possession of weapons, violence can serve as a collective pastime. And for that umpteenth teenager who was found dead next to the military base where the soldiers born in Sri Lanka or Montevideo or anywhere else in the world were kept, what need for tenderness or money or maybe for travel pushed him into the arms of his rapists? Between Julio, the most solitary boy of Burial Street, who hides the fact that he doesn’t like girls from others and from himself—because even on our street, overpopulated by the living and the dead, there’s a place for secrets—and the boys who sleep in the beds of service members in need of exercise and high-ranking officials of the Occupation, will any of them ever be the masters of their desires and bodies? And the pretty spokeswoman from Toronto or Clermont-Ferrand who will placate the media, talking about the investigation currently underway into the teenager’s death and of the first findings which, of course, point to a suicide—at what age did she learn to lie? Does she also lie about her loves and desires? What is being? Between a journey that ends in catastrophe, or a collapse right where one already is, what is the heaviest kind of defeat? What future awaits a girl who grew up on Burial Street, with dead people rotting in the tombs of the great cemetery for neighbors? I am thinking of Sophonie and Joëlle, the two women I love. I believe that I’ve always loved them, without ever feeling the need to choose between them, or even get too close to them. What kind of future will they forge for themselves? I am thinking, too, of the little brunette who works for the United Nations civilian mission, the one I watch every Wednesday, so sad and so proud at the wheel of her service vehicle. What path of arrogance and depression did she follow to get from her Parisian suburb to her current position, from her childhood to the Wednesday nights drinking beer at Kannjawou, the restaurant-bar? And me—where am I going? For the moment, I’m living through this journal, which I keep in order to stay focused on my occupied city and on my neighborhood, which is inhabited by as many dead people as living ones, as well as the comings and goings of the thousands of strangers I come across, and those of the ones I’ve never really come across. You can make out only their outlines behind the tinted windows of their luxury cars and official vehicles. Today, I’m idling on my sidewalk curb, playing at being a philosopher. But tomorrow, who will I be? And how will I, like everyone else, live truth and falsehood, and strength and cowardice, at the same time? Which self do you end up becoming, and at the end of which path?

THE LITTLE PROFESSOR ARRIVED FROM ANOTHER ERA AND ANOTHER NEIGHBORHOOD WITH THE SAME QUESTIONS. And in the evenings, when he leaves me on my sidewalk

curb and returns to the solitude of the library, I know that he is bringing our questions with him. I stay and listen to the sounds of the cemetery. If I ever write a novel, as Mam Jeanne, Sophonie, and the little professor have suggested, the cemetery will be its main character. All major characters have two lives, two faces. The cemetery has two lives. One of them, the official one, is during the day. With funeral processions. Grief laid bare to the commotion of the crowds. The speeches of officials. Instructions for standards, order, positions. Fanfares and grand scenes of despair, like a big street theater play where everyone knows exactly what his or her role is: the moment when this lady should lose her hat, or that one should lift her arms to the sky. The schedules that dead people and their companions must follow. During the daytime, the cemetery is careful to preserve its image, just like a person. But in the evenings when the shows are over, it has another life. A more secret one, but more a truthful one, too. A crazy one. The pickaxes of the grave-robbers. Their pranks. Their laughs, sometimes, a little noise so that they can breathe, for silence makes death feel all too present. The shadows who murmur prayers to gods who can’t be called upon in front of everybody. The homeless people or thugs who pile into tombs that they refer to as their “apartments”. The black candles. Mam Jeanne tells us that once upon a time, after the sun had set, ministers and generals and artists and businessmen would often come to the paths of the great cemetery. Talent pillagers, who would spoil the grave-robbers’ job prospects by seizing one or another corpse in particular in order to take away a part of its body—a hand, if he had written well, or its better foot, if he had played soccer—and wield it like a talisman. It is a weakness of the living to want to usurp the qualities of the dead. Accompanied by sidekicks—magicians and professional killers—they came to assure themselves that this enemy or that rival would never be seen again, or to try to extort the secret of their success from their dead body. Apparently, even foreign dignitaries would come to steal ideas from dead geniuses. The craziest beliefs and the most perverse vices are universal. But these days, talent pillagers have become rare. Our dead people no longer hold any appeal. The rich, the gifted, and the other high-quality people have left to die somewhere else. Wealth and poverty, and success and failure, have always been waging warfare here. The richer I am, the farther away I go. Catch me if you can. The great cemetery isn’t the resting place for great men anymore. Its new inhabitants and their visitors are unknown people with ordinary lives. The only ones buried there are the lesser people, dead of ordinary sicknesses that a doctor would have been able to cure. Little, unimportant corpses, who invented nothing and don’t deserve a place in the shackles of memory.

I’VE HAD THIS HABIT OF KEEPING A JOURNAL SINCE CHILDHOOD. For my sixth birthday, Sophonie gave me a notebook. Sophonie has always had the gift of being one step ahead of others, understanding their needs and expectations even before they do. I remember that there was a lion on the cover and that my classmates laughed at it. Writing is not in fashion on Burial Street. It’s a rare type of madness, and spending time far away from the commotion of parties and brawls makes you a kind of foreigner. During my childhood I would go seek refuge at Mam Jeanne’s house so that I could write. She let me scribble whatever I wanted in silence. But then the moment would come when she couldn’t stop herself from talking about the first Occupation. She didn’t call it “the first” because she wasn’t expecting a second one. I’ll never forget the day when the foreign troops arrived. She shut herself up in her room with her cat, Loyal, and didn’t utter a single word the whole day. I think it was the only day I’ve ever seen her cry. I was thirteen years old. I had never seen so many weapons and tanks outside of movies. Popol, Wodné, and Sophonie tried to mobilize the young people, telling them: we must do something. Joëlle and I followed them without knowing what to say. We didn’t speak the right language. Two or three years can make a big difference when it comes to mobilizing. “Mobilization” was the rallying cry, but we didn’t “mobilize” as such. The adults—the shoemaker, the undertakers, the akasan* vendor, the old bookbinder who already had very few old books to bind—demanded that we leave them the hell alone, shouting to us that there wasn’t anything left to preserve. Not dreams. Not dignity. The kids threatened to smash our faces in. Only Julio had accepted our invitation. He prefers boys, but not shaved heads. There weren’t many voices of protest. It was as though people had gone to bed. As though it was the whole world that had taken possession of our streets. The occupiers’ ruse was the abundance of flags, colors, uniforms. The friendly smiles of the generals and the spokespeople. Their rhetoric of friendship and multilingualism. How can you revolt against an enemy that’s constantly changing its tone and its face? Of all the kinds of unhappiness, without a doubt, the worst is powerlessness. Everything played out above our heads. Both literally and figuratively. Planes and helicopters. And the heads of state who had said yes, you can come to our country. And the private English and Spanish teachers who were suddenly now making a fortune. Popol, Sophonie, and Wodné, who led Joëlle and me, weren’t taking the failure of their first initiative well. When you’re fifteen years old and love your country, you might then wonder, what kind of temple is it when its caretakers turn into doormats, brown-nosers? Ten years later, that feeling of abandonment—and above all, that anger—hasn’t ever left us. Anger about everything, angry at everyone and at ourselves. This anger will kill us, or will cause us to kill, maybe, taking aim at the wrong target. I think, too, that powerlessness has divided us a little bit. It was at that time that Popol and Wodné had their first conflicts. Before, nothing had ever separated them. Defeat brings with it division, and the end of any lost battle brings reproach for any fellow fighter who didn’t fight well enough. Out of all the adults, Mam Jeanne was the only one to really welcome us. On the night of the landing, she had come out of her room, motioned to us to come inside, offered us tea, and said, “My little ones, this is a land without anyone in charge. Look at these people marching in the street. No one is watching over them; no one’s fighting for them. And it’s always been like that. So all these vultures come to prey on them. You will suffer. We will all suffer. And suffering needs air, it needs space. You can spit on it or you can suffocate. So, when it comes time to spit, don’t go after the wrong target.”

WHEN YOU’RE ANGRY OR ALONE IN AN IMPASSE, YOU BELIEVE THAT THINGS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN THE SAME. Exhausted from constantly searching for the right words or a good attitude, Mam Jeanne sometimes wails that it’s always been the same, ever since her childhood. And yet she’s the one who told me that even underneath what seems like emptiness, there is movement. She’s the one who told me about the resistance efforts against the first Occupation. She’s the one who told me not to spit on the wrong targets. You can’t ask someone—even a force like Mam Jeanne—to be one hundred percent clear-sighted twenty-four hours of the day. We’re all allowed to get a little worn down. When Popol, Wodné, and Sophonie began to take an interest in politics, they did some research. Joëlle and I followed them everywhere, in their footsteps and in their thoughts. That was how we learned the history of the lost battles, the sacrificed lives, the efforts of those who had dreamed of a better life for everyone. Always. Before, after, and during the periods of dictatorship. Before, during, and after the first Occupation. There had always been brave souls to say no. The little professor had fought, too, in his own way. In the corner of his library, he has an old mimeograph machine, like a relic from another era, and I assume that it was used to print illicit pamphlets and newspapers. I also once met an old man at his house who doesn’t talk very much. But I know who he is: Monsieur Laventure. The dictatorship had stolen his wife from him. He spent three years in prison. No one had seen him since his incarceration, and everyone believed him to be dead. But one day, he came back to life. Skinny. A matchstick of a man. He had been kept in isolation. His “widow” had married his best friend and his oldest comrade-in-arms. They are still together, and he has stayed alone, all while taking up t

he fight again by their side. I’m afraid to approach him, and have never dared ask the little professor to make introductions. It’s not easy to see a legend, a hero who has led a life of battle and sacrifice, up close. That’s how he’s spoken of in the progressive circles at the university. I don’t know what there is between him and the little professor. The little professor has never described himself as a “militant”. A bit of mystery resides in even the most open of people. And for them, secrecy was how they survived. They’ve held on to their reflexes from times past. During the dictatorship, if you spoke, you died. The little professor tells us with a smile how, in his youth, when there were more than three of them and one of them was keeping quiet—even if they were talking about soccer or their studies or love affairs—the others would ask him to open his mouth and say something, anything. A joke about the weather, a psalm, a La Fontaine fable. Because if the secret police arrested them after their conversation, the torturers would ask them to report exactly what each of them had said. “You have to say something, so that the others don’t have to invent something, or be beaten, for your silence.” Today, you can speak. Everyone speaks. A teacher who’s more preoccupied with his career than with the lives of others can play at being a revolutionary during class. On every street corner is a man or a woman who harangues the people hurrying by. The Occupation’s civilian staff has multiplied the number of conferences and seminars that obedient job seekers can attend. There’s no shortage of declarations of intention. You even hear, ten years too late, voices denouncing the occupiers. Everyone speaks. And words allow you to score a few points in the scramble to look good. That’s called democracy. If you lie, everyone listens to you. If you tell the truth, no one will listen to you anymore. They’ll respond to you with the gentle voice of a pretty, tanned spokesperson, saying that it’s nice that you’re expressing yourself. But the guns remain. And the tanks. And the unhappiness. And it’s still every man for himself. These days, it’s crazy what people talk about, but does talking still serve any purpose? Sometimes, the little professor and I fall into silence on my sidewalk curb. I love that man, but deep down, I don’t know him well and I still don’t understand him. I could ask him, too, about the unplanned paths that people wind up following. It’s true that he comes from the other side of town, and here, every neighborhood is a little world with its own laws and codes.

Kannjawou

Kannjawou