- Home

- Lyonel Trouillot

Kannjawou Page 4

Kannjawou Read online

Page 4

MY BROTHER AND I ONLY REALLY TALK ON WEDNESDAY EVENINGS. It’s the most crowded night, when the bar is open late. A flood of aid workers from all the Organizations-Without-Borders, allied countries, Occupation personnel, and young bourgeois are there. It’s a night of dancing and it lasts for a long time. We go together to wait for Sophonie, so that we can accompany her home after the bar closes. It’s all that’s left of the long walks of long ago. Of the lightness of times past. Going as a pair. And returning as a trio. Could it be that all the steps of our childhood—when Sophonie freed the lizards and dragonflies that Wodné had tied to a string; when we looked for hidden places in the sea where we could learn to swim, naked; when life was nothing but a big kannjawou, for Anselme, Mam Jeanne, the old people, the young people, all the Burial Streets and everyone from every corner of the world; when I learned from Wodné and Popol words whose meanings I didn’t know but which sounded like promises—were nothing but lost steps?

THERE ARE SOME EVENINGS WHEN MAM JEANNE CALLS DOWN FROM HER BALCONY TO INVITE THE LITTLE PROFESSOR AND ME TO COME UP AND HAVE SOME TEA WITH HER. To talk to us about the past. Mam Jeanne is the doyenne of Burial Street. Only the cemetery was born before her. In her stories, the past is all bric-a-brac. Everything is jumbled together. The time when women couldn’t enter the old cathedral without missals and mantillas, and would be pardoned for their adultery if they made substantial donations to the archdiocese treasury. The time of matinees at the Cinema Parisiana, tissues in hand for the tears brought on by an Italian actor, Amedeo Nazarro, who always played the son of a nobody and with whom all the young girls were in love. The time of the railroad, whose trains transported more cargo than passengers. The time when trees bloomed on Center Street, attracting turtledoves and wood pigeons, before the prison was built. The time when the Palais Orchestra performed on the Champ-de-Mars on Sundays, alternating waltzes, contra dancing, and military marches. In Mam Jeanne’s stories, the past will never be over. It will last for an eternity, distinct from the present. It’s difficult for her to match dates to facts. In order to recall the month or even the year, she has to think about it, count on her fingers. Except when she talks to us about the first Occupation. “There was nothing worse.” Not the yaws epidemic, when the disease attacked the feet and arms of the poor. In the countryside, no one dared any longer to clasp a friend’s hand, kiss his fiancée, drink from the same cup as his neighbor. Nor Hurricane Hazel. The crops and livestock carried away by the wind. The convoys of clothes and food sent to the flooded areas, which were held up for several days by the violence of the swollen rivers carrying trees and livestock. Nor the years that were unreasonably dry. The adults threw their hands up to the sky. And the children’s hungry eyes leaked tears of dust. “Yes, there was all of that. But the worst was when the boots came.”

HISTORY ISN’T ONLY MADE UP OF CATASTROPHES. In Mam Jeanne’s memories, there were also a lot of joyful times. In the past, there were plenty of kannjawous. “Circuses. Amusement park rides. Carnival parades, when those were still an attraction. With stilts as high as tall houses. Masks, both funny ones and not-so-funny ones: General Charles Oscar, bloodthirsty rapist, who died by the sword, just as he had lived. Beautiful Choucoune with the legendary ass, the mixed-race woman who had ruled over the hearts of the seaside shopkeepers, and who alone caused more suicides and bankruptcies than a financial crisis. Queens, each one prettier than the last. How beautiful it all was! The inauguration of the International Exposition. In ’49, I think. The singer Lumane Casimir, the most beautiful voice we had ever heard here. And the first jet of the illuminated fountain. The crowd was amazed and let out a cry of “Ah!” as though they had witnessed a miracle. The parade with horses. And the sports contests, the dances, the bursts of fireworks.” But the most beautiful of all was the departure of the Marines. “Even the funeral processions felt joyful. Here, on Burial Street, the children gave out sticks with ribbons attached that were the color of the flag, and the parents used them to decorate the coffins of their dearly departed. I don’t believe in ghosts, but it seemed to me as though there were songs of rejoicing coming from the great cemetery. Even the dead were celebrating that day.”

She says this, and is then overcome by sadness. They came back. This time, when they entered, they didn’t kill anyone. Not the little heroic soldier. Nor the rebellious farmers. Nor the ordinary citizens shot down by wayward bullets or drunken Marines who didn’t appreciate the muted anger in their eyes. They came back. They had meetings and conferences, agreements and resolutions made by do-gooder assemblies. They came back, with pretty spokespeople you could fall in love with. Men with crazy hair who don’t seem all that bad and who smoke joints with the other people their age. With little brunettes with wounded eyes who seem to be doing so badly that you want to feel sorry for them. But as Mam Jeanne says, “Foreign boots are foreign boots. On the ground, they’re all the same heavy footsteps.”

MAM JEANNE CLAIMS THAT IT’S A STROKE OF LUCK TO LIVE ON A STREET THAT ENDS WITH DEAD PEOPLE. It makes you learn very quickly how to distinguish what is real from what is false. Every day there’s a parade before us of dead people sealed up in their coffins. We don’t see their faces. But we see the faces of the living people who accompany them. And Mam Jeanne wants the things that are happening in your heart to show up on your face. According to her, even the most naïve of kids can see, if he looks closely, which widow’s face is covered in real tears for a useless dead man whom she nevertheless continues to love. Which loved ones or friends are focused on something else and finding the time slow to pass. Which group of dice players knows that for all of them their luck has just changed, that from now on life is nothing but a slow slip into death, the partner that they’re burying only the first in a long series. Which screams from a prodigal son ring false, and are all a sham.

LOOKING CLOSELY, YOU CAN SEE THAT JOËLLE DOESN’T HATE THE LITTLE PROFESSOR. In fact, she’s the only one to call him by his first name, Jacques. And in the evenings, she comes to join our conversation, faking a nonchalant walk that doesn’t hide the fact that she’s hurrying. Only for a few sentences. I give them a moment alone, claiming to have an errand to do in the neighborhood or some work to finish. It’s crazy how much she looks then like the little mischievous girl who, almost twenty years ago, on one July morning, had suggested that we go see the hurricane up close. Anselme already wasn’t walking too well at that time, but he was managing okay with his cards. He was still feeding his children by selling the future to people begging for miracles. He was getting out of bed only to receive clients. His cards next to him on the bedside table, he believed strongly in the power of speech. He expected the things he said to come true as much as his clients did. Disappointed clients sometimes returned to him with insults and demands for reimbursement, as his quack predictions had never materialized, or the opposite had come true. The pretty woman he had predicted would come to the lonely man hurting for love had turned out to be a shrew. The handsome man actually a bully. Wealth actually grinding poverty. This or that announced trip had turned into a never-ending wait, despite the sums of money paid to myriad brokers and officials. He gave the money back with excuses. Reality had lied. For Anselme, words create the world. It was enough for him to say, “One day, I’ll get my land back and we will have the most beautiful kannjawou, my daughters,” then wait for the day to arrive. Sophonie was skeptical. Anselme hadn’t seen Immacula’s death, nor the more ordinary problems, coming. He couldn’t see that he would never manage to take back the land that had been taken from him by shady lawyers and the henchmen of whatever despot had been in power at the time. That his daughters weren’t farmer princesses at all, and would have to fight to survive. That even if these mythical lands did exist, they wouldn’t know what to do with them. That they were daughters of Burial Street, second-class citizens who would know neither sowing and harvest nor the luxuries of hilltop mansions. Anselme hadn’t seen the occupiers’ boots coming, nor the civilian staff who would go drinki

ng at Kannjawou. A seer who had been struck by blindness. A fallen wealthy farmer who had failed on Burial Street. But Joëlle believed in her father’s predictions. Gullible little girls don’t listen to the news. To convince her of his powers, he informed her of what everyone else already knew: that a hurricane was coming. “Tomorrow. Don’t be scared. You see, your father knows everything that is to come.” Wind wouldn’t do any harm to his children, especially not to his favorite one. And so according to Joëlle, who was firm in her convictions, we could go see the hurricane up close. And even if it might be risky, it would be worth it to see what was in the middle of the wind. I loved that expression: in the middle of the wind. I had written it down in my notebook, and sometimes, to remember the gang of five, I reopen that notebook to the page with the middle of the wind. Wodné didn’t think that it was wise to go see the hurricane closer up. Popol didn’t say anything. Joëlle insisted. It’s not good to be afraid. Sophonie decided that we would go, to please her little sister. And also to defy Wodné. We went out into the street. The wind struck us in the face, but we could still see the outlines of each house and walk in the rain. In the beginning it was very pleasant. If that’s what they call danger… But then, very quickly, the wind pushed us in the direction of the cemetery. Impossible to resist, to choose our own path, to turn back. The wind brought us to where the dead were resting. The left-hand side of the great gate had been ripped away and was being pulled towards the inside of the cemetery as though it were as light as a feather. The water ran and covered the pathways. The new tombs, whose cement hadn’t yet fully dried, had turned into little ponds. When the middle of the wind arrived, it was a frenzied madness that left nothing in its wake and swept everything on the earth up towards the sky; the water that came crashing into our eyes made the horizon disappear. Groping for shelter, we hid in an unlocked vault that had been under construction. Together, holding each other’s hands, we held the gate in place. In front of us floated coffins that looked like crazy boats. We waited. Fortunately, the middle of the wind was moving. After several hours, it left to go elsewhere. We walked in the mud and rain, trying to avoid stepping on the bodies and thousands of objects that the storm had lifted from their tombs. The hurricane had done more in several hours than Halefort’s gang had in years. We didn’t want to split up or go to Wodné’s aunt’s house or to the girls’ house, where Anselme was probably asleep and dreaming of kannjawou, or to our house, where in any case there weren’t any adults. So we took shelter in Mam Jeanne’s house, spending the night there. Joëlle hadn’t trembled or whined. She’d wanted to see and she had seen. We had gone into the middle of the wind and we came back out again. It’s that Joëlle that I leave in the little professor’s company in the evenings. A little girl with lively eyes, asking to see. Their conversation never lasts very long. Wodné is always there, watching over them. Joëlle rejoins him silently. Then I walk a little longer with the little professor, up until College Street. Then I go on my own way. We walk in opposite directions, but the ends of our nights are similar. It’s the time when we become our dreams and spend a long time with characters from books. If we must, as Wodné says, always find a difference, it’s just that the little professor has more characters in his house than I do in my room.

IS WHAT IS TRUE FOR PROCESSIONS ALSO TRUE FOR BARS? Seated on the low wall that borders the courtyard of kannjawou, I like to observe the clientele. On Wednesdays, when Popol and I go to wait for Sophonie, Monsieur Régis, the owner of the bar, allows us to sit on the wall and have one beer each. He’s not a bad guy. The staff members like him. He has a sense of humor. “With what I charge my clientele, I can afford to give you a beer.” It’s the third bar that he’s opened. The first two didn’t work out very well. After those two failures, he learned. A residential neighborhood. A name that’s a little mysterious: “Kannjawou”. Shadowy corners. Music that they’ll like. Wait for the first foreigner. “Since they’re all attracted to the idea of being an explorer—we’ve known that since Christopher Columbus—the first one will bring another. The second will bring a third. Life is good in the New World.” Monsieur Régis is a beefy guy, a force of nature with a tendency to gain weight and go running on Saturdays. “A restaurant owner shouldn’t be either too fat or too thin. Too fat, you look sleazy. Too skinny, you look stingy. I like to stay between the two.” His wife’s name is Isabella. She calls him on the phone twenty times every night, and he responds that he should have done as his best friend, who lasted only a week in the bonds of marriage, did. Go far away, like Christopher Columbus did. Because it’s no treat to answer the same questions every evening. “How many patrons tonight? Are the servers looking presentable?” Nor is it fun to live under such financial surveillance. Monsieur Régis doesn’t have a cent to himself. “It’s Isabella who holds onto the money. Because of her name, she thinks she’s a queen. And she’s Catholic, as the other Isabella was. Except that unlike King Ferdinand, I have no ships, I’ll be forever in debt thanks to this bar, and no one’s yet offered to make me a saint.”

From our wall, we watch Sophonie fuss around, going from one table to the next, smiling at her customers, pretending not to notice our presence. “At the bar, I’m working. The smiles are for the customers.” This is what she says. But most of the customers don’t even notice that she’s smiling at them. She serves them drinks at least once a week, but when they pass her in the street they don’t recognize her. It doesn’t matter. Sophonie has always done things just because they seem right to her. Necessary. This job is for Anselme. And for Joëlle, who will show them. So, no matter if the customers can be crude. And all things considered, there’s little chance that she’ll run into any one of them anywhere but the bar. After closing time, they head out in groups towards their apartments or houses in chintzy neighborhoods, at the wheels of their cars, which are draped in the colors of international institutions or NGOs. Their journeys will end at the top of some hill or another. And not a sad, ramshackle hill, shaking with the coughs of tuberculosis, like the ones that loom over the cemetery and shelter the sanatorium, where the poor people who are going to die from some contagious disease are hidden away. Nice hills, with their own names that start with “Belle”—Bellevue, Belleville—at the end of a private street, protected by sentry boxes, watchdogs, and security guards. They come down to the bar to slum it. Outside of those escapades, many of them only know the upper part of the city. That expression, the upper part of the city, comes from one of the bar’s customers, one of the few with literary alcoholism: he tends to rhapsodize about literature whenever he drinks. Monsieur Vallières, who thinks his ravings are an important piece of work, he says that, like the human body, cities are divided in two parts: upper and lower. The problem is when the line of demarcation is lost. “Tell me. Can you still tell who is who here?” He drinks too much and talks a lot. Words tussle with each other in his mouth. Too many things come out at the same time. Bickering. Contradicting each other. They say he failed at his career as a Latin scholar. Thanks to a family inheritance, he owns a store that he runs in the old-fashioned way, to the great despair of his sons. In his family, he plays the role of intermediary between his father, who imposes his will with the power of his legacy and his strength of character and who had wanted his son to become a man of great refinement, and his sons, unsophisticated bloodsuckers whom he refers to as garbage. The bar is his theater. Strangely enough, it’s also a form of resistance for him. He often raises his voice. This bothers the younger members of the Occupation staff, who don’t like to hear any voices other than their own and the racket of the music they’re dancing to. He looks at them and shouts, “Aren’t I at home here?” Monsieur Régis likes him very much and sometimes sits down at his table. Monsieur Vallières takes advantage of this when it happens, retelling his memories as an egghead and a scholar. Literature, fancy language. Entire pages of Historia. The Renaissance, revolutions, Genghis Khan and Mata Hari. The other customers, the younger ones—aid workers, or children of wealthy parent

s—avoid him and don’t talk as much, or in any case not about things like the Renaissance, revolutions, Genghis Khan and Mata Hari. Wodné would say that Monsieur Vallières is an old bourgeois, distrusted by young people because he hasn’t learned how to adapt to modernity. I personally believe that at the rate they’re drinking, they’re running away from him because he looks like he could be their future. At least, if any of them know how to read things other than relationships and instructions. For lack of an audience, he sometimes invites us to sit with him at his table. Even if you’re rich and cultured, you do what you can with what you have. Two little guys from Burial Street might be interesting and make very nice substitutes if the only other audience you have is the least sophisticated members of the middle class and arrogant technocrats, the civil arm of the Occupation. His madness makes him pragmatic. Although Popol and I are only pretending to listen to him, Monsieur Vallières appreciates the company of us representatives of the “lower parts”.

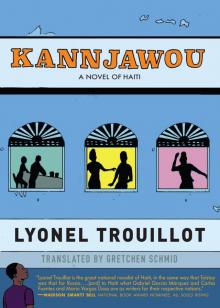

Kannjawou

Kannjawou